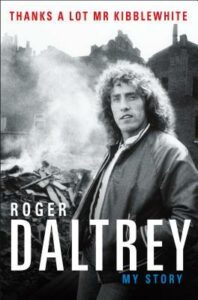

What I’m Reading: Thanks a Lot Mr. Kibblewhite

|

| My friend Jen clipped this from Seventeen magazine for me. |

I’ve been a passionate fan of The Who since I was in high school: when all of my peers were swooning over the New Kids on the Block, I was obsessively watching old Who music videos and the Ken Russell film version of “Tommy” — and nursing a huge crush on the golden-haired, steel-throated Roger Daltrey (never mind that he was old enough to be my dad). After reading Pete Townshend’s autobiography “Who I Am” (while wishing, to be honest, that he would write less about himself and more about the band), I was excited to learn that Daltrey was releasing his own book and I would finally get to hear him tell The Who’s story in his own words. What I learned from “Thanks a Lot Mr. Kibblewhite” was that phrases like “never meet your idols” and “careful what you wish for” gained popularity for a reason.

There’s a lot to like here: While some rock memoirs spend way too long on the early years (Townshend’s even tells his parents’ life stories, as if we care), this one gets right to the good stuff, interspersing anecdotes from The Who’s heyday throughout the sections on Roger’s childhood and adolescence. And Daltrey’s dry wit is evident throughout, as when recalling this exchange with a doctor:

“So, Mr. Daltrey, when did you break your back?” he asked. Politely, I pointed out that I hadn’t. Politely, he pointed out that I had. He had the evidence, right there on the X-ray — one previously broken back, one not very careful owner.

But the overall tone of the book is defensive, starting right from the title — which is a snarky backhand at an old headmaster who told young Roger he’d never amount to anything — and continuing throughout. Many passages seem written for no other purpose than to get in a dig at Townshend. Though Daltrey frequently refers to Pete’s talent and good intentions, he also doesn’t spare the snark. For instance, of The Who’s 1989 reunion tour, he writes:

Pete spent most of the tour playing acoustic guitar. He got someone else in to play the electric. He even thought about playing in a glass box to protect his hearing. I wish I could have got someone else to sing my bits. I would be very happy, standing there, doing the odd harmony. But that’s what Pete wanted and I just gave in.

And recalling an incident in which Pete swung a guitar at Roger’s head and Roger responded by punching Pete in the face, he writes:

I was the one who had been attacked, but somehow I ended up feeling responsible. … Thankfully, Pete survived, but for the rest of my life I’ve had to listen to him blaming me for the bald spot on the top of his head. To this day, I think he believes I was the aggressor but this is how I remember it.

Then there’s the matter of Daltrey’s family life. In writing about his second marriage, to Heather — whom he describes as the love of his life (his first marriage having been in response to an unplanned pregnancy) — he makes no bones about the fact that he was unfaithful to her. In fact, before he would marry her, she had to agree that it was fine for him to sleep with other women while he was on tour. This arrangement resulted in four illegitimate children (that he knows about), which he refers to as his “surprise children.” Of them, he simply states, “We’re very good friends and I love them all, but I’ll be completely honest, I don’t feel the same way about them as I do about the children I had with Heather.” Though many reviewers have praised him for being frank and candid, to me that came off as a bit heartless.

Daltrey is at his most sympathetic when recalling his relationship with the band’s tormented jester, drummer Keith Moon. Despite his lack of patience with Moon’s infamous hotel-trashing antics, the two developed a close friendship that persisted until the end of Moon’s life. When Moon was at his lowest, he would call Daltrey at 4 a.m., knowing Roger would answer when no one else would. “Heather was particularly good with him in that dark period, and we did what we could,” Daltrey writes. “Of course, for the last four decades, I’ve spent a lot of time wishing I’d done more.” (Oddly, Daltrey and Townshend give conflicting accounts, in their respective memoirs, of how they found out about Moon’s death in 1978; each says that the other called him with the news.)

In addition to being immensely talented, it’s obvious that Daltrey has a stellar work ethic, and there are hints throughout “Kibblewhite” — such as his tenderness toward Moon and his later charity work for the Teenage Cancer Trust — that he has a good heart as well. Unfortunately, for most of the book he really comes off as an entitled jerk, whether he’s recounting how he walked out or delivered ultimatums in order to forcibly push The Who in the right creative direction, lambasting Townshend for his spinelessness, bitching about bassist John Entwistle’s relentlessly loud amplifier, or taking a mocking tone when describing the failure of replacement drummer Kenney Jones to emulate Moon’s signature style. I guess he’s only human — and I’m still a fan — but my inner 15-year-old died a little while reading this memoir, disillusioned that my British rock god wasn’t the gallant prince I’d hoped he would be.

Footnote: As an accompaniment to this book, I highly recommend listening to Consequence of Sound’s Discography podcast. While “Kibblewhite” glosses over much of the actual music of The Who, Discography host Marc With a C delves track by track, album by album, into the band’s entire catalogue and even their solo records, providing a lot of context to Daltrey’s memories and creating a more layered narrative.

Nicely done!

Thanks! If you like rock memoirs (and aren't as invested), it's definitely entertaining and worth a read.

Very interesting!